Women & Work - the stories we followed in April 2025

News, research, data, and recommendations about women and work - curated by our team

Hello, and welcome to CEDA’s newsletter ‘Women & Work’!

April brings with it new beginnings — the start of a financial year and a renewed focus on the systems that shape our working lives. As we publish this edition on International Workers' Day (Labour Day), we’re reminded of the collective efforts that sustain our economies, and the importance of ensuring that women’s work — paid and unpaid — is visible, valued, and supported. We’ve gathered some of the key updates and conversations that stood out to us this month. We hope you enjoy reading and reflecting with us.

Before we get started, a request: We are curating ‘Women & Work’ with the hope that it can provoke, stimulate and amplify conversations about women’s participation in paid work in India. If you like this edition, please do share it on your social media, and with your friends, family and colleagues. Thank you.

In case you would like to read any of our past editions, they are available here.

🗞️In The News

ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activists) workers are a vital part of India’s public healthcare system, delivering essential services such as maternal and child healthcare, immunisation, and health education in rural and underserved areas. In Kerala, ASHA workers have been protesting for over 70 days, calling for fair compensation, retirement benefits, and formal recognition as workers. Read more to understand their fight and the changes they are advocating for.

The PM Internship Scheme, designed to connect the youth from low-income backgrounds with leading companies, revealed a concerning gender gap, with women making up just 28% of participants in its pilot phase. Key barriers-including low stipends, unsafe travel options, and the concentration of internships in major cities with limited affordable and safe accommodation, have disproportionately impacted women, especially those from rural areas. Read more about how these early-stage challenges have limited women's access to valuable career opportunities here.

Does the controversy surrounding The Great Indian Kitchen or its Hindi remake Mrs. seem like an exaggerated version of reality? The data says otherwise. According to the 2024 Time Use Survey, Indian women continue to bear a staggering burden of unpaid domestic labour, averaging over seven hours daily—more than twice the amount men spend. A recent Reddit discussion on India’s love for freshly cooked meals, later featured by The Economic Times, sparked a wave of reflection on how deeply this cultural norm continues to burden working women.

The 2025 India Justice Report lays bare the stark gender gap in India’s police forces—women make up just 12 percent of the force, with 90 percent in lower-tier constabulary roles, and only 8 percent in leadership positions. Despite mandated quotas, not a single state or union territory meets its target, highlighting the structural barriers to achieving gender equity in policing. For an overview of the key findings, refer to the article summarising the report.

💡Research Spotlight

The “motherhood penalty” is a well-documented reality in labour markets around the world—women with children often face slower career progression, fewer callbacks, and lower pay. But there's a group whose experience is rarely spotlighted in data or policy debates: single mothers. A recent study by Somdeep Chatterjee, Ralitza Dimova and Shubham Ojha takes this conversation further by examining how employers in India respond to women who are raising children without partners.

How did the researchers measure discrimination?

To isolate employer bias, the researchers used a correspondence testing experiment—a field method often used in labour economics to detect hiring discrimination. Here’s how they designed it:

Fictitious resumes were created for women with identical education, skills, and work experience. The only variables that changed were marital and parental status.

Applications were sent to over 1,000 real job vacancies in entry-level private sector roles such as retail, IT, and banking.

Each resume indicated the applicant’s marital and parental status, such as through personal statements (e.g., “living with spouse and two children”) or emergency contact details.

The experiment compared four applicant profiles: unmarried women without children, married women without children, married mothers, and single mothers, revealing the impact of family status on employers' responses and shedding light on the deep-seated biases influencing hiring decisions.

What did they find? A steep hierarchy of bias

Despite identical qualifications, the callback rates showed stark differences:

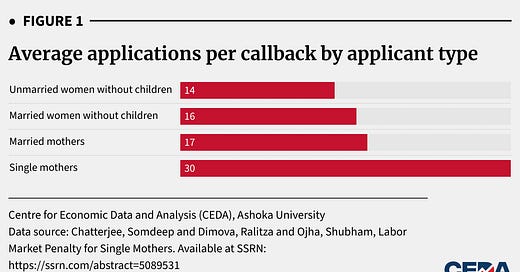

Figure 1 highlights the challenges single mothers face in the job market, requiring them to submit more than twice as many job applications as unmarried women without children to secure a single interview.

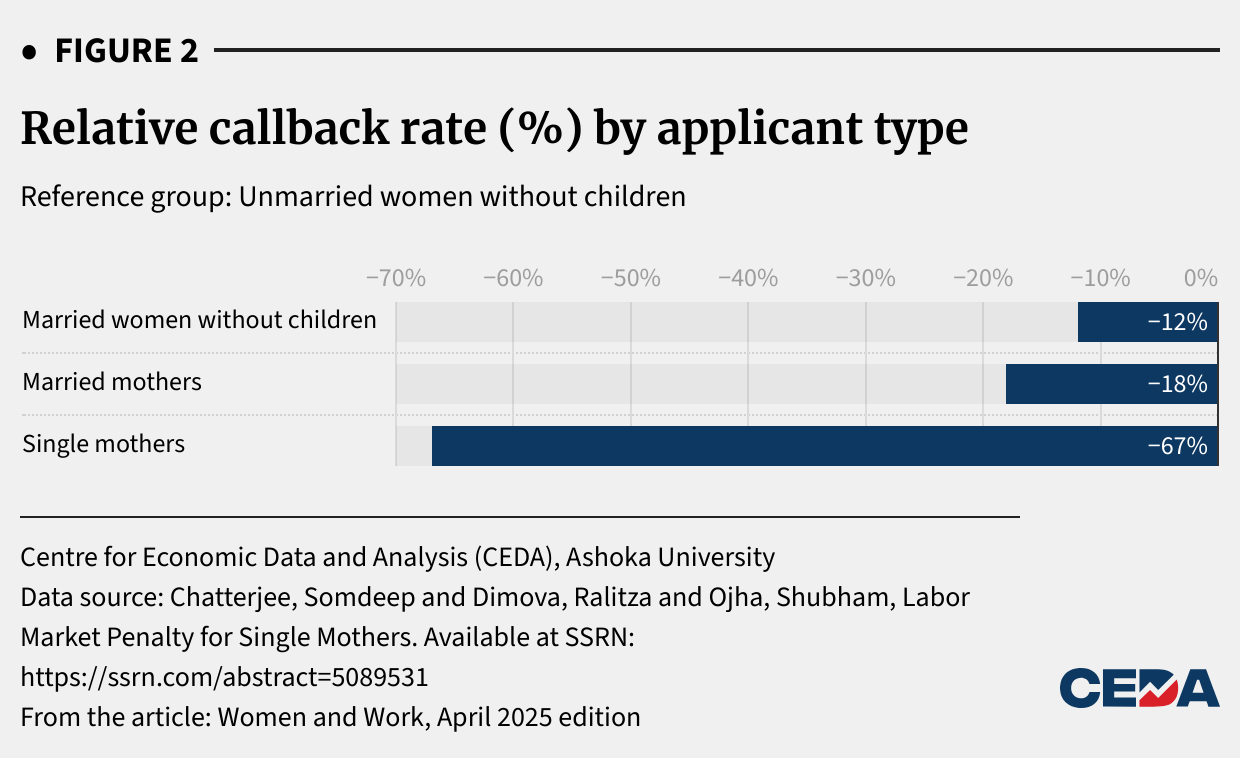

When compared to the reference group, unmarried women without children, the relative callback rate for single mothers drops by 67 percent (Figure 2). This is a far steeper penalty than the 12 percent drop observed for married women without children and the 18 percent drop for married mothers. These findings underscore a double disadvantage: both marital and parental status exacerbate the already significant motherhood penalty. As a result, single mothers face disproportionately higher employment barriers, even when their credentials are comparable to those of other women.

Digging deeper: why are employers biased?

The study uncovers two key mechanisms fueling the discrimination faced by single mothers in the labour market. First, statistical discrimination suggests that employers view single mothers as less reliable or as less flexible, especially for roles that demand relocation or irregular hours. For jobs requiring travel, callback rates for single mothers dropped an additional 30 percent. Second, implicit bias plays a significant role, as revealed by a vignette survey of business students—the future HR professionals. The results showed that 44 percent of respondents believed employers saw single mothers as unstable, while 41 percent attributed the bias to assumptions about lower productivity. These biases are not grounded in the applicants’ qualifications but instead arise from deep-rooted societal norms, where marriage is often seen as a symbol of stability, unfairly influencing hiring decisions.

To delve deeper into the findings and methodology of this study, explore the full paper available here.

📊Datapoint

The data from the 2023 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), visualised through CEDA's Socio-Economic Data Portal (SEDP), presents a concerning wage gap between Scheduled Caste (SC) women and women in the general category (Others) across all states in India. National average daily wages reveal that SC women in regular salaried jobs earn only half of what women in the general category make. This stark disparity reflects the persistent socio-economic inequalities and systemic discrimination faced by SC women in India's labour market, severely restricting their access to fair wages and equal economic opportunities.

The SEDP portal provides a powerful tool for exploring and analysing socio-economic data at the state and district-level across a range of sectors including health, education, and employment. Use SEDP to uncover critical socio-economic trends and drive informed decisions in research, policy, and advocacy. Explore here.

👍 CEDA Recommends

This edition’s recommendations have been curated especially for our readers by Dr. Aparna Vaidik, Professor of History, Ashoka University.

What’s an essential academic work that you would recommend to someone who is just getting started with working on the subject of female labour force participation?

I would recommend two essays by historian Joan W. Scott: “On Language, Gender, and Working-Class History” (International Labor and Working-Class History 31, 1987) and “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis” (in Gender and the Politics of History, New York: Columbia University Press, 1988).

In the first article, Joan Scott critiques two foundational works on socialist and labour history – E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (Vintage Books, 1966) and Gareth Stedman Jones’ The Languages of Class: Studies in English Working-Class History, 1832-1982 (1983). According to Scott, both historians have a gendered understanding of class – that is, the ‘class’ they are analysing is primarily male. She demonstrates that the histories of the making of the English class are premised on the binary that sees productive relations in factories as primarily masculine and, in contrast, the domestic sphere of labour as feminine; it is the former that is seen as the foundation of class consciousness. Furthermore, the language of socialism also inadvertently reinforced gendered power relations and inequities. What happens to women and their labour in such an analysis? In Scott’s view, they are either relegated to partial and imperfect political actors in the masculine sphere of activity or represented as a regressive element that is detrimental to class politics.

In the second article, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis”, Scott puts forward a more comprehensive understanding of gender as a category of analysis. According to her, gender can be seen as having four integral components: its symbolic representation, the normative concepts used to interpret it, its politics within social institutions and organisations, and its existence as a subjective identity.

Anything published in the news media recently that shed light on an important aspect about women’s work in India?

I follow the Instagram handle @iseesomeletters, run by Aleena, a Dalit poet, lyricist, and artist from Kerala. As a Dalit woman from a historically marginalised background, her presence and voice are, in and of themselves, important women’s work. She uses the digital space to write about the structural and interpersonal aspects of caste and the ways it determines social, political, and economic life in the subcontinent. For instance, in one post, she says: “ For women in general, it’s ‘go back to the kitchen.’ For me, a Dalit woman, it is ‘stay in someone else’s kitchen’. ”

Is there a film that you can recommend which, in your opinion, does a good job of portraying the world of work from a gender lens?

The Hindi film Nil Battey Sannata (which translates as “zero divided by zero is nothing,” or colloquially, “good for nothing”) was directed by Ashwini Iyer Tiwari in 2015 and stars Swara Bhaskar. It is a poignant story that revolves around the life of a domestic worker, Chanda, who is a school dropout but wishes for her daughter, Apu, to stay in school. However, Apu is unmotivated and unable to envision a future in which she is anything other than a domestic worker. To inspire and teach her daughter, Chanda herself enrols in school to learn mathematics. Apu is embarrassed by this and begins to treat her mother unkindly, but Chanda refuses to back down. She promises Apu that she will drop out if Apu does well in her exams, but ultimately breaks her promise and continues to study. Both mother and daughter complete their senior secondary exams together. Eventually, Apu grows up to become an IAS officer, and Chanda becomes a tutor for children who struggle with mathematics. The film is a commentary on the social lives of female domestic workers, their struggles, and their dreams.

And a book that did the same?

Ila Arab Mehta’s Fence (translated by Prof. Rita Kothari) tells the story of Fateema, a lower-class Muslim woman who works as a history lecturer. Fateema has the usual aspirations: to have a job, to be independent, and to own a home. But achieving these dreams requires her to break through the ‘fences’ of social prejudice. Living in a state marked by communal strife, her aspirations become the reason she is ridiculed within her own community. Yet, she continues to persevere.

⏳Throwback

Drawing inspiration from this insightful article, we revisit how Indian advertisements mirrored global patterns in presenting household tech — not as liberators, but as enhancers of domestic productivity. While innovations like washing machines and pressure cookers promised efficiency, they rarely translated into less work for women. As researcher Valerie Ramey observed, even major technological advances did not reduce women’s time on housework — instead, they just shifted the nature of tasks.

A 1960s Prestige pressure cooker ad, for example, promises “more money” and “more time for other useful work” — but leaves the nature of that "work" conspicuously undefined. Instead, it features a cheerful woman still firmly placed in the kitchen, reinforcing domesticity as her domain.

Fast forward to the 1990s, and a Videocon washing machine ad echoes a similar narrative—offering women ‘freedom’ that simply repackages unpaid care work. Instead of opening doors to leisure or opportunity, the ad shows a woman tending to children and serving elders—her day merely reorganised, not relieved.

Source: PaletteAdFilms, "Videocon Washing Machine," via YouTube.

These ads didn’t promise fewer chores, just more efficient ones. The rewards? A spotless home, happy family, and the quiet dignity of doing it all — efficiently. Despite the promise of time-saving technologies, women’s unpaid labour continues to be reframed, not reduced, reinforcing the idea that women’s work — even when ‘freed up’ by technology — still revolves around invisible labour.

Thank you for reading! If you have feedback, questions, tips, or just want to say hello, feel free to do so by replying to this email, or drop in a word at editorial.ceda@ashoka.edu.in

For more updates and conversations, be sure to follow us on LinkedIn and X. We look forward to staying connected with you!

Curated by: Sneha Mariam Thomas for the Centre for Economic Data & Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University. Cover illustration: Nithya Subramanian