Women & Work - what we’ve been tracking through July 2024

News, research, data, and recommendations about women and work - curated by our team

Hello, and welcome to CEDA’s newsletter ‘Women & Work’!

Jobs, employment and skilling have been the flavour of the month as India’s Finance Minister acknowledged and prioritised these while presenting the Union Budget for FY 2024-25. We bring you the details on that, and a lot more in this month’s edition. We hope you’ll enjoy reading the same!

Before we get started, a request: We are curating ‘Women & Work’ with the hope that it can provoke, stimulate and amplify conversations about women’s participation in paid work in India. If you like this edition, please do share it on your social media, and with your friends, family and colleagues. Thank you.

🗞️In The News

The Indian government wants to facilitate higher participation of women in the workforce. To this end, the Indian Finance Minister announced multiple initiatives while presenting the Union Budget for FY 2024-25 in the Parliament earlier this month. These include setting up of working women’s hostels in close collaboration with industries, setting up of creches, women-specific skilling programmes, and promotion of market access for women SHG enterprises.

In the run-up to the Union Budget, the government also released the Economic Survey for 2023-24. It has a dedicated chapter on employment and skill development, with a focus on youth and female labour force participation. The survey argues that the recent rise in the LFPR of women, especially in rural areas, is not out of distress, and acknowledges systematic barriers such as legal prohibitions that inhibit job opportunities for women. Lastly, it identifies agro-processing and care economy as two promising candidates for future job creation, noting that the latter is also a “necessity for levelling the playing field for women in labour market”.

Our take: CEDA welcomes the official acknowledgement of the serious and urgent issues around (the lack of) productive and remunerative employment opportunities that affects both men and women, but the barriers are especially onerous for women. Recognising the problem is indeed the first necessary step towards outlining a set of solutions. We hope this long overdue recognition will also be backed by a concerted policy framework that would help relax barriers that women face: transportation, lack of a care infrastructure, access to piped gas and water that would lower their time on domestic work. Most critically, we will need to focus on job creation in rural India, where women have very few productive paid work opportunities. Seven percent: that’s the share of women-led businesses among all outstanding loans to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), according to Niraj Nigam, executive director at Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Business Standard reported. This is much lower than the share of women-led businesses among all MSMEs (about 20 percent). There is a range of reasons contributing to this – from structural issues like low level of capital, low rates of labour force participation, societal norms like restricting women from inheriting property. All this limits women’s ability to show collateral for lending and also inhibits access to education and training. It also leads to the "stereotyping" of women borrowers by financiers, like them being considered as higher risks, leading to higher interest rates, greater insistence on collateral or outright rejection of loan applications. Read more here.

Several global brands are shifting their manufacturing process to India in a bid to reduce their dependence on China, a New York Times news report notes. This could open up several manufacturing jobs, especially for women. Read more here.

💡Research Spotlight

Economic crises, such as the recent Covid-19 pandemic, often have long-term consequences for labour markets, economies and workers. Young people who enter the labour force during such extraordinary times may be especially vulnerable and face greater challenges in finding good opportunities.

In an earlier edition, we had written about research from Latin America that looked at how economic crises impact the long-term labour market outcomes for men and women differently. This month we bring you a recent World Bank working paper by researchers S Anukriti, Catalina Herrera-Almanza and Sophie Ochmann, who surveyed young women from Haryana to understand the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the labour market aspirations and expectations of young women in India.

Their findings are based on a survey of 3,180 female students (average age 22 years) enrolled in their final year of training at various Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) in Haryana. The data was collected between June and August 2022.

This is what they find:

Young women want to work: Nearly all respondents (95 percent) said they wanted to work after graduating from their ITI program.

Not only is there a clear willingness to work, almost half of the respondents expressed willingness to migrate to a different city or town for work if their salary increased by INR 5,000.

The pandemic seems to have had a sobering impact on the young women’s aspirations. The exposure to the Covid-19 pandemic decreased the wage aspirations of young women living in rural areas by 25 percent, the researchers find. Economic research has found that young people tend to have high expectations of a “reservation wage” (i.e. the minimum wage at which they are willing to work). In that sense, the pandemic may have turned the wage aspiration more realistic for these women, the authors argue.

Further, the pandemic reduced rural women’s willingness to migrate for work by 65 percent (there was no similar impact on urban women, however).

“This decline in the desire to migrate could be driven by a decrease in the expected net benefit from migration due to greater uncertainty, fear of job loss, lower chances of reintegration, and lack of social security in the event of another Covid-19 wave,” the authors note.

So overall, what does the study find?

The good part is that the willingness to work remained high for these young women, even though the pandemic may have lowered their wage aspirations. But the risk, the authors caution, is that such a correction could “have a negative consequence for women’s agency related to work decisions—this is because the decrease in their willingness to migrate is likely to decrease their expected income (and hence their agency) given that migration to urban areas is an important pathway to higher incomes for many rural households.”

The story is complex, and still unfolding. Read the full paper here.

📊Datapoint

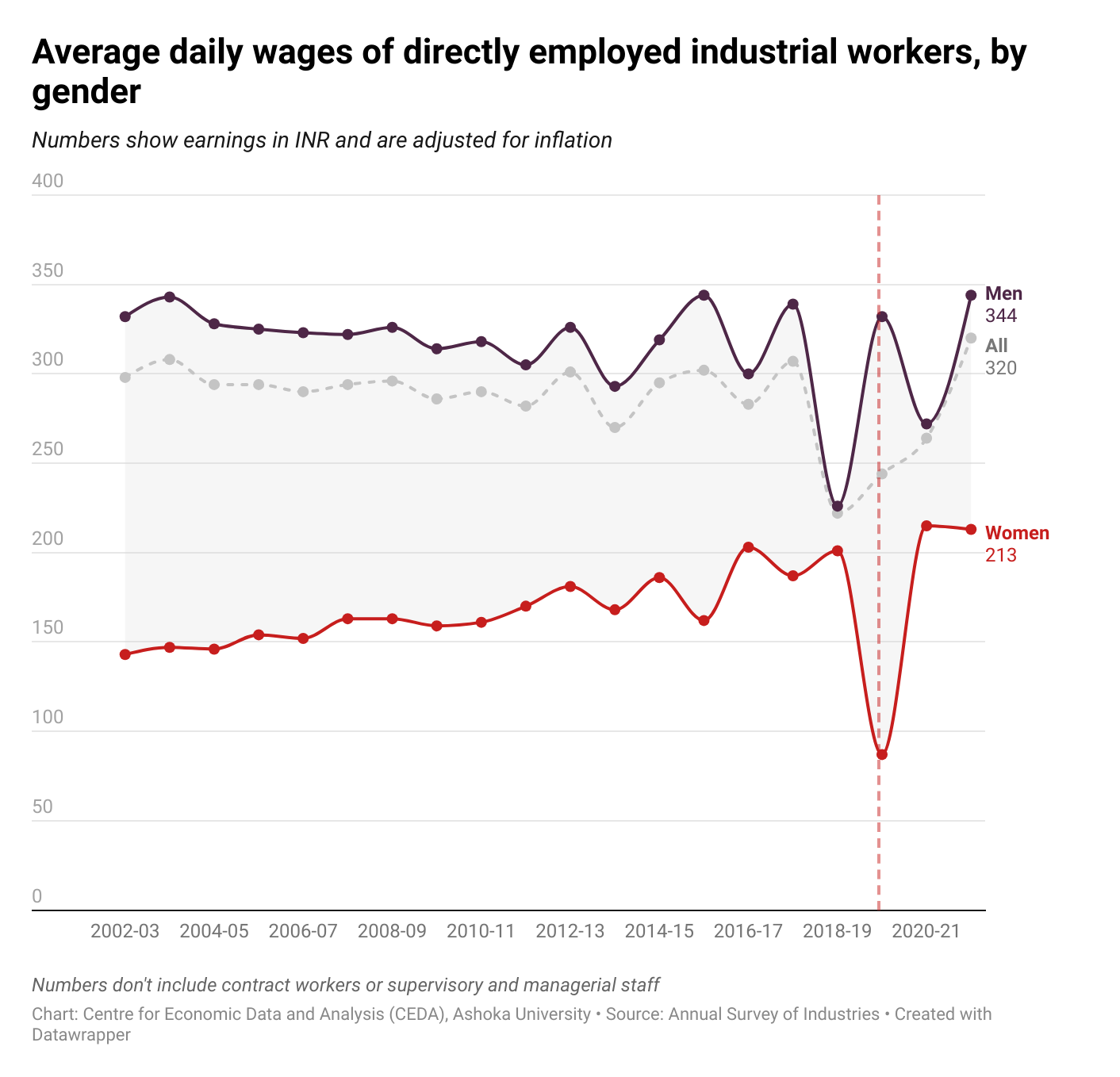

A factory floor worker employed directly by factories in India’s formal manufacturing sector earned INR 586 as daily wage on average in 2021-22, data from the Annual Survey of Industries shows. While male workers earned INR 630, female workers earned only INR 389 on average. Further, if we adjust earnings for inflation, we find that while women’s wages have witnessed a higher compounded annual growth rate as compared to that of men between 2002-03 and 2021-22, the gender wage gap continues to be wide. (Analysis by Kulvinder Singh/CEDA).

👍 CEDA Recommends

This edition’s recommendations have been curated especially for our readers by Ayush Pant, Assistant Professor of Economics at Ashoka University.

What’s an essential academic work that you would recommend to someone who is just getting started with working on the subject of female labour force participation?

Ayush Pant: Most academic discourse about female labour force participation in India centres around getting women to work. While relevant social and economic constraints restrict women's labour force participation and need our attention, an equally important and less explored question deals with keeping women at work, particularly in developing countries.

A severe impediment could be harassment at the workplace—verbal, physical, or sexual—that makes women quit their jobs and the labour force. What can be done about this issue? Bourdeau, Chassang, Gonzales-Torres, and Heath (2024) provide one possible solution in a paper titled `Monitoring Harassment in Organizations.' In this highly influential work, the authors show that switching some (random) subset of reports of not having faced harassment to having faced harassment can significantly improve the reporting of such crimes. Since harassing seniors can retaliate, such a switch provides the harassed individuals with plausible deniability, thereby reducing the risk of retaliation. The authors test the effectiveness of this mechanism relative to others in an RCT in large Bangladeshi garment factories and find that it "increases reporting of physical harassment by 290 percent, sexual harassment by 271 percent, and threatening behavior by 45 percent, from reporting rates of 1.5 percent, 1.8 percent, and 9.9 percent, respectively, under the status quo of direct elicitation." Their theory further offers ways of estimating policy-relevant statistics of harassment, such as its prevalence, who is responsible for such misbehaviour, etc, from the collected data.

As a side note, this paper is a beautiful example of how theorists and empiricists can work together to answer socially relevant questions and provide scientific answers that can potentially positively change people's lives.

Anything published in the news media recently that shed light on an important aspect about women’s work in India?

Professor Farzana Afridi wrote this opinion piece a month before the election results were released, highlighting the importance of increasing women's labour force participation to attain the Viksit Bharat 2047 vision. Her column identifies three areas our government needs to focus on -- increasing manufacturing jobs, upskilling women, and making cities safer for women. While the latter two are fine suggestions, some economists have critiqued the strategy of making India the world's manufacturing hub. Historically, the path to the development of many economies is usually laid by building the manufacturing sector.

However, as Raghuram Rajan and Rohit Lamba argue in their book Breaking the Mould, India may have missed the boat on this one. They suggest an alternative path of building India's services sector and leveraging its comparative advantage in the tech industry. If the government were to adopt this alternative path, it would be worthwhile weeding out gender disparities in educational outcomes and spending more on women's education, fixing the capability deprivation of women from a younger age.

Is there a film that you can recommend which, in your opinion, does a good job of portraying the world of work from a gender lens?

Given my appetite for shows and movies, I can probably recommend quite a few. Parks and Recreation (2009-15), Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (2015-19), The Morning Show (2019-), Blue Eye Samurai (2023-), and Panchayat (2020-) are just a few with strong women characters who operate within the bounds placed by the society and chart their territories. Since Panchayat is fresh in my mind, I will discuss it more. I would argue that Panchayat is as much a show about Manju Devi's journey of finding her voice as Sachiv Ji's journey of becoming one with a more significant cause. From being a Sarpanch merely in the namesake to plotting and scheming and trusting her intuition to preserve her position, she has had quite a journey in the show. Yet, as a reminder that she is still a product of the society she lives in, she only desires to see her daughter get married and is unwilling to see what value can come from her getting a job.

And a book that did the same?

I'm a big fan of Lady Mariko and Lady Ochiban's characters from Shogun (1975) by James Clavell. I would not want to give any spoilers here, but suffice it to say that I can write an entire essay on these two tragic characters. As each tries to achieve their single-track goals in a Samurai-infested blood-soaked mediaeval Japan where women exist only to expand the bloodline, the two women's destinies come to be intertwined from a very young age.

⏳Throwback

Women remain a minority among workers in India’s factories – comprising roughly a fifth of the workforce in India’s formal industrial sector, CEDA has noted previously. How was the situation a few decades ago?

Different, but not so much. As this clipping from the Annual Survey of Industries of 1959 shows, the share of hours put in by women workers in the total number of worker hours was less than 15 percent (13.3 percent).

That’s all from us for this edition. Thank you for reading! We will see you next month. In the meantime, if you have feedback, questions, tips, or just want to say hello, feel free to do so by replying to this email, or drop in a word at editorial.ceda@ashoka.edu.in

Curated by: Akshi Chawla for the Centre for Economic Data & Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University. Cover illustration: Nithya Subramanian