Women & Work - what caught our eye in October 2023

News, research, data, and recommendations about women and work - curated by our team

Hello, and welcome to CEDA’s newsletter ‘Women & Work’!

It’s been a *BIG* month. The Nobel prize, the women’s strike in Iceland, lots of data releases – a melange of developments that have turned the spotlight on women’s work from various (all critical) vantage points. Needless to say, we have been breathlessly tracking all the developments, and we have tried to pack as much as we could in this edition. Happy reading!

To everyone who is new here: We curate ‘Women & Work’ with the hope that it can provoke, stimulate and amplify conversations about women’s participation in paid work in India.

You can access previous editions of this newsletter here. Please help us reach more readers by sharing this edition on your social media, and with your friends, family and colleagues. Thank you!

🗞️In The News

First up, the Nobel! The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences (the Nobel prize for Economics) for 2023 has been awarded to economist Claudia Goldin “for having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”.

Credit: The Nobel Prize’s page on social media platform X As the award announcement notes, Goldin’s research provided the first comprehensive account of women’s earnings and labour market participation through the centuries. Read this piece in The Indian Express where Ashwini Deshpande, our Academic Director, expresses the hope that the award will push economists to acknowledge that labour-markets are not gender-neutral.

Equally inspiring has been the Nobel Prize in medicine to Katalin Karikó (along with Drew Weissman) for their research that enabled the development of effective mRNA vaccines against Covid-19, as well as the peace prize to Human Rights Activist Narges Mohammadi for her fight against the oppression of women in Iran and her fight to promote human rights and freedom for all.

India’s female labour force participation rates have seen some improvement, data from the latest round of the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) released this month shows. Over a third (34.1 percent) of women aged 15-59 were part of the labour force in 2022-23, as compared to 29.4 percent in 2021-22. However, only 18.9 percent of women who were part of the workforce were engaged in salaried work, while 63.3 percent were self-employed (the corresponding shares for 2021-22 were 20.3 percent and 60 percent respectively).

Improving women’s labour force participation from the current rates to about 50 percent can add one percentage point to India’s GDP growth, Auguste Tano Kouame, the World Bank’s India Director said in an interview to the publication Mint earlier this month.

“That alone will almost be enough to help India achieve an 8 percent growth rate, without even spending more on equipment, capital or whatever. That low-hanging fruit to me is the biggest opportunity for India to achieve its target growth rate,” he further added. Read the full interview here.

Just about a quarter of employees in India’s top 100 listed firms are women, an analysis of data from company annual reports by Mint has found. Among companies for which data is available for each of the last three financial years, this share has improved from 24.6 percent in 2021 to 27.9 percent in FY 2023. Not only are there few women working in the crème de la crème of India Inc, they are also more likely to be quitting jobs. The median attrition rate of male employees of BSE 100 firms was 16.6 percent in the year ended 31 March. For women, the corresponding attrition rate was 19 percent.

A similar analysis of 1,040 companies by EY shows that women’s representation is better among permanent employees, as compared to their representation among workers, the Business Standard reported. While 23 percent of permanent employees of the firms were women, women made up only 11 percent of workers in FY 2023.

Mahindra & Mahindra has announced a new maternity support policy for its employees that spans a 5-year period from pre-childbirth to the time the child turns 3. The company will henceforth provide support during pregnancy (commute reimbursement during the last trimester), for IVF treatments (75 percent cost support for two IVF cycles), paid maternity leave for 26 weeks even in cases of adoption and surrogacy, flexible work options for up to 3 years post childbirth, childcare support allowance till the child turns two along with other support mechanisms.

Ruzbeh Irani, President, Group HR, Mahindra Group, said that the policy was inspired by the fact that they did not want women to feel that they have “to make a choice between their careers and their family life.” Read more here and here.

Madhya Pradesh has announced a 35 percent quota for women in all government jobs in the state (except the forest department), and a 50 percent quota in teaching jobs. Read more here.

In the USA, three women and a non-profit have filed a hiring discrimination lawsuit with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against a major trucking company to challenge the company’s same-sex training policy. Stevens Transport, one of the largest refrigerated trucking companies in the USA, follows a training policy that allows women drivers to train only under women trainers. Since they do not have adequate female trainers, this essentially means that fewer women are hired, and hiring of women is often delayed. The three complainants had applied for a job with the company after the company advertised immediate openings, but were eventually denied the positions because the company did not have female staff to train them. Read more about the lawsuit and the gender-gaps among truck drivers in the USA.

💡Research Spotlight

“For the vast majority of hiring decisions around the world, meritocracy is an insidious myth. It is a myth that provides cover to institutional white male bias,” writes Caroline Criado-Perez in “The Myth of Meritocracy” in her book, Invisible Women.

In celebration of Claudia Goldin’s Nobel Prize, in this edition we turn the spotlight on one of her seminal papers published in 2000 in the American Economic Review that provided evidence about this very myth.

Using historical data from actual orchestra auditions from the USA, Goldin and her co-author Cecilia Rouse demonstrated that a simple design change in the audition process increased the chances of women being hired.

What was this design change? “Blind” or “screened” auditions where the jury could not see the candidate but only hear the music. As Criado-Perez notes, a simple step that turned the audition process into a meritocracy.

Goldin and Rouse begin their paper by observing that while “sex-biassed hiring has been alleged for many occupations” it is “extremely difficult to prove”.

Using data from auditions of eight major symphony orchestras in the USA from the late 1950s to 1995, Goldin and Rouse found that adding a screen and making it a blind audition increased the probability that a female candidate would move forward from the preliminary round of the audition by 50 percent. The screening also increased the likelihood of women getting selected in the final rounds of the audition.

In addition to audition data, Goldin and Rouse also studied roster data of eleven major symphony orchestras. They found, again, that a shift to blind auditions was able to explain 30 percent of the increase in the proportion of women among new hires and “possibly 25 percent of the increase in the percentage of women in the orchestras between 1970 to 1996”.

“Although some of our estimates have large standard errors and there is one persistent effect in the opposite direction, the weight of the evidence suggests that the blind audition procedure fostered impartiality in hiring and increased the proportion [of] women in symphony orchestras,” the authors add.

Read the full paper here.

📊Datapoint

38.3 percent of women workers (aged 15-59) in rural areas worked as unpaid helpers in 2022-23, data from the most recent round of the Periodic Labour Force Survey shows. Five years ago, this share was 33.1 percent. Among their male counterparts, the share of those working as unpaid helpers was 10.6 percent. The share of the urban workforce working as an unpaid helper is smaller as compared to the rural workforce. But here too, a clear gender gap exists. In 2022-23, only 4.5 percent of male workers aged 15-59 worked as unpaid helpers, while among urban women of the same age group, this share was 11.4 percent. (Analysis: Kulvinder Singh/CEDA)

👍 CEDA Recommends

This edition’s recommendations have been curated especially for our readers by Srijita Ghosh, Assistant Professor of Economics at Ashoka University

What’s an essential academic work that you would recommend to someone who is just getting started with working on the subject of female labour force participation?

Srijita Ghosh: The paper that got me interested in the question of female labour force participation is "Culture: An Empirical Investigation of Beliefs, Work, and Fertility" By Raquel Fernández and Alessandra Fogli (link). The authors delved into the role of culture defined as a set of beliefs and preferences in determining the female labour force participation decision. This raises a crucial supply-side issue related to FLFP that is often difficult to operationalize and requires innovative use of existing datasets.

A related paper that has stayed with me is “Marrying Your Mom: Preference Transmission and Women's Labor and Education Choices” by Fernández, Fogli, and Olivetti (link). It is an interesting paper that describes the nuances of family-level supply-side factors in determining female labour force participation.

Anything published in the news media recently that shed light on an important aspect about women’s work in India?

This article in the NPR succinctly portrays the dilemma of women, specifically middle-class women, in the labour market. Going with the theme of supply-side issues related to female labour force participation this article describes how women's decision to work is considered as supplementary to men's work. An implication of this is that women’s work is often considered as an indicator of financial hardship in the family. On the other hand, the job of caregiving is by default considered women’s work. Thus an increase in demand for caregiving work often forces women out of the labour market.

Is there a film that you can recommend which, in your opinion, does a good job of portraying the world of work from a gender lens?

A TV show that I'd recommend to watch would be Agent Carter in the Marvel series. In the Marvel universe of superheroes, Peggy Carter is a special agent whose calm demeanour is deceptive of her strength. Throughout the show, the creators have well portrayed the struggle of a woman in a position of power. Set in the aftermath of WWII, this action-filled show highlights issues in the workplace that today's women who work in traditionally male jobs can relate to.

And a book that did the same?

One of my favourite authors of all time is Leo Tolstoy. His treatment of female characters has always surprised me. His bright, full-of-life, talented female protagonists always find fulfilment only by taking the role of a wife and a mother. And any deviation from said role always ends up in tragedy.

One of the prime examples is Natasha Rostova in War and Peace. After exploring various subplots with the character the author finally puts his judgement by making her a completely devoted wife and mother and the reader is perplexed by the sudden transformation of a woman who so far in the novel has never displayed any inclination towards such roles. Tolstoy reflects the mentality of his time where the only role of a woman was that of a caregiver and she could have been considered successful only in that role. Even though centuries have passed since the time of Tolstoy the expectations regarding the role of women in caregiving have not changed much. Reading such classics would make us ponder the successes and failures of the movement that has helped women come out of the primary role of caregiver and make use of their full potential.

⏳Throwback

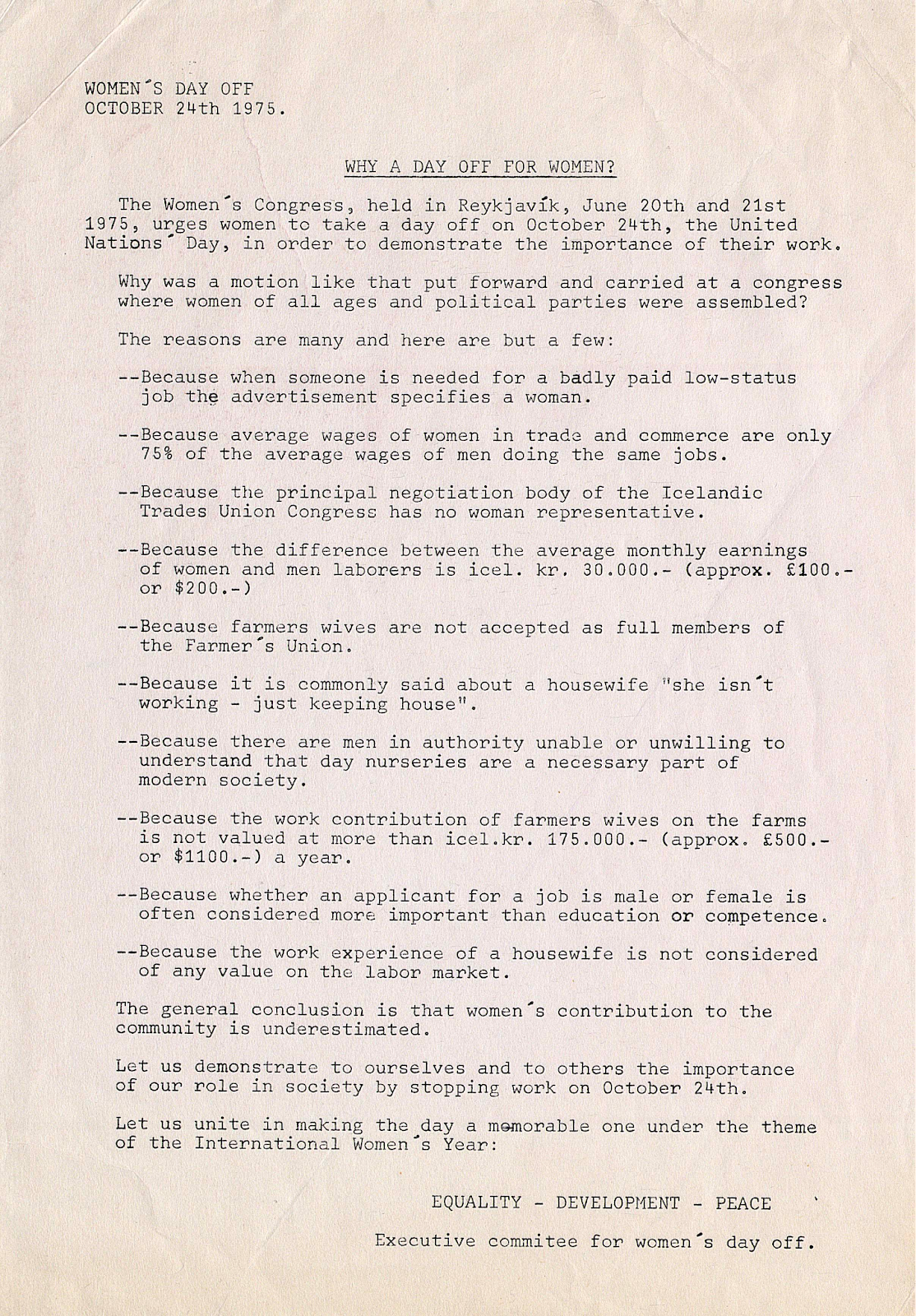

On October 24, Iceland’s women, including their Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdóttir, went on a strike to demand wage equality and an end to gender-based violence.

The day marked the 48th anniversary of a landmark strike that has played a pivotal role in the country’s socio-economic progress. On October 24, 1975, women in Iceland took a day off from work as part of a strike that became a watershed moment in the country’s history.

Organised with the aim to demonstrate the critical contribution of women to the country’s economy and society, as well as to protest against wage discrepancies and unfair employment practices, the strike went on to become a huge success with an estimated 90 percent of the country’s women participating in it.

Women took a day off from all kinds of work, including domestic and household work. Several services were impacted as a result. Several factories, banks and shops had to close. The newspaper edition of the day was considerably shorter. Many schools were closed or worked at reduced capacity. Flights had to be cancelled.

Fathers had to bring their children to work. Children’s voices could be heard in the background as news readers read the news on radio.

An estimated 25,000 women also participated in a mass gathering in the country’s capital, Reykjavik. It was attended by women from all walks of life, including two women MPs.

A year later, the country passed the Gender Equality Act that prohibited gender-based discrimination. Five years later, Vigdis Finnbogadottir was elected the country’s President, another historic milestone (not only for Iceland, but for the world). She went on to serve 16 years in office. Several other milestones have followed in the years ever since. Over the years, Iceland has made significant progress on closing the gender gaps in several areas of socio-economic life, and has been consistently ranked the best in terms of gender equality.

Read more about the historic strike here.

That’s all from us for this edition. Thank you for reading! We will see you next month. In the meantime, if you have feedback, questions, tips, or just want to say hello, feel free to do so by replying to this email, or drop in a word at editorial.ceda@ashoka.edu.in.

Curated by: Akshi Chawla for the Centre for Economic Data & Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University. Cover illustration: Nithya Subramanian