Women & Work - what caught our attention in October 2024

News, research, data, and recommendations about women and work - curated by our team

Hello, and welcome to CEDA’s newsletter ‘Women & Work’!

🪔As we brace ourselves for Diwali festivities, we are here in your inbox a day earlier with all the important updates about women’s participation in the economy. We hope you will find this edition useful.

In case you would like to read any of our past editions, they are available here.

Before we get started, a request: We are curating ‘Women & Work’ with the hope that it can provoke, stimulate and amplify conversations about women’s participation in paid work in India. If you like this edition, please do share it on your social media, and with your friends, family and colleagues. Thank you.

🗞️In The News

The South Asian region has among the lowest rates of female labour force participation in the world. The World Bank’s latest South Asia Development Update, ‘Women, jobs and growth’ flags this, observing that the shortfall in the female labour force in the region is most pronounced after marriage. “On average, once married, women in South Asia reduce their participation in the workforce by 12 percentage points, even before they have children,” the report notes. The Bank argues that raising the participation rate of women to equal that of men could boost per capita incomes in the region by as much as 51 percent, but this would require efforts from all parts of the society. Access and read the report here.

“Maharashtra’s Ladli Bahin Yojna, aimed at empowering women through financial incentives, is impacting cotton farming in the state by weaning women off farms, creating labour shortage and driving up harvesting costs,” argues a report in Mint. Eligible beneficiaries receive a financial assistance of INR 1,500 per month under the scheme. Due to this, many are not taking up cotton harvesting work, driving up labour shortages, says the report. Read here.

Our take: Media reports indicate that the scheme has been received with enthusiasm which highlights the need for financial assistance for the vast majority of families that are in informal work. The fact that a meagre INR 1,500 per month is pulling women out of harvesting work makes one wonder how low the remuneration must be for such work.In the meanwhile, a report in The Hindu from a different part of the country offers some explanations for that. Reported from various parts of Tamil Nadu, they find persistent wage gaps between men and women across the state. If for construction work a man makes INR 800 per day, a female worker makes only INR 350. While men engaged in agricultural work earn INR 350 per day, women earn only INR 160. Further, the state Gazette classifies work as skilled or unskilled, and often puts work performed by men as skilled and that by women under unskilled, despite the kind of labour involved in many of these tasks. Read the full report here.

💡Research Spotlight

Globally, only 17.8 percent of businesses are owned by women, data from the World Bank shows. Further, while women make up 23 percent of employees in firms owned by men, this share is 42 percent in firms owned by women. And while only 6.5 percent of firms owned by men have women as their top managers, this share is more than 50 percent for women-owned businesses.

Against this backdrop, Gaurav Chiplunkar and Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg studied and developed a framework for quantifying barriers to labour force participation and entrepreneurship faced by women in India.

Representational image. Credits: Pau Casals/Unsplash

They have some important findings:

Women face substantially higher costs of labour force participation as well as for expanding their businesses.

The one (and only) area where women entrepreneurs have a clear and significant advantage over their male peers is the employment of women workers (particularly in the informal sector.

Conditional on female labour force participation, the constraints on expanding a business (what economists would call the “intensive margin”) are more severe than the constraints on entering entrepreneurship (in technical terms the “extensive margin”). Basically, it is easier for women to enter businesses but much more difficult to expand these businesses.

These are findings based on the study’s model developed using data from two waves of the Economic Census (1998 and 2005).

So what are the implications of this? Chiplunkar and Goldberg argue:

Policies that target aspects of the intensive margin (like hiring barriers or costs) are likely to have substantially larger effects than those that simply focus on entry costs.

Policies promoting women’s entrepreneurship are recommended – they can have large effects on improving women’s labour force participation (not only by facilitating more women to become entrepreneurs but because they are likely to hire more women workers).

Policies must focus on improving the demand for women workers – otherwise simply focus on increasing labour force participation can lead to a decrease in the real wages of women.

Main takeaway: Designing for policies that can enable more women entrepreneurship is important. However, these should not be limited only to getting women to enter entrepreneurship but should focus on helping the women expand their enterprises. It boosts labour force participation of women, but it is good for the economy too (by enabling high-productive, marginal entrepreneurs to enter, and thereby mitigating misallocation of resources to low-productivity entrepreneurs).

📊Datapoint

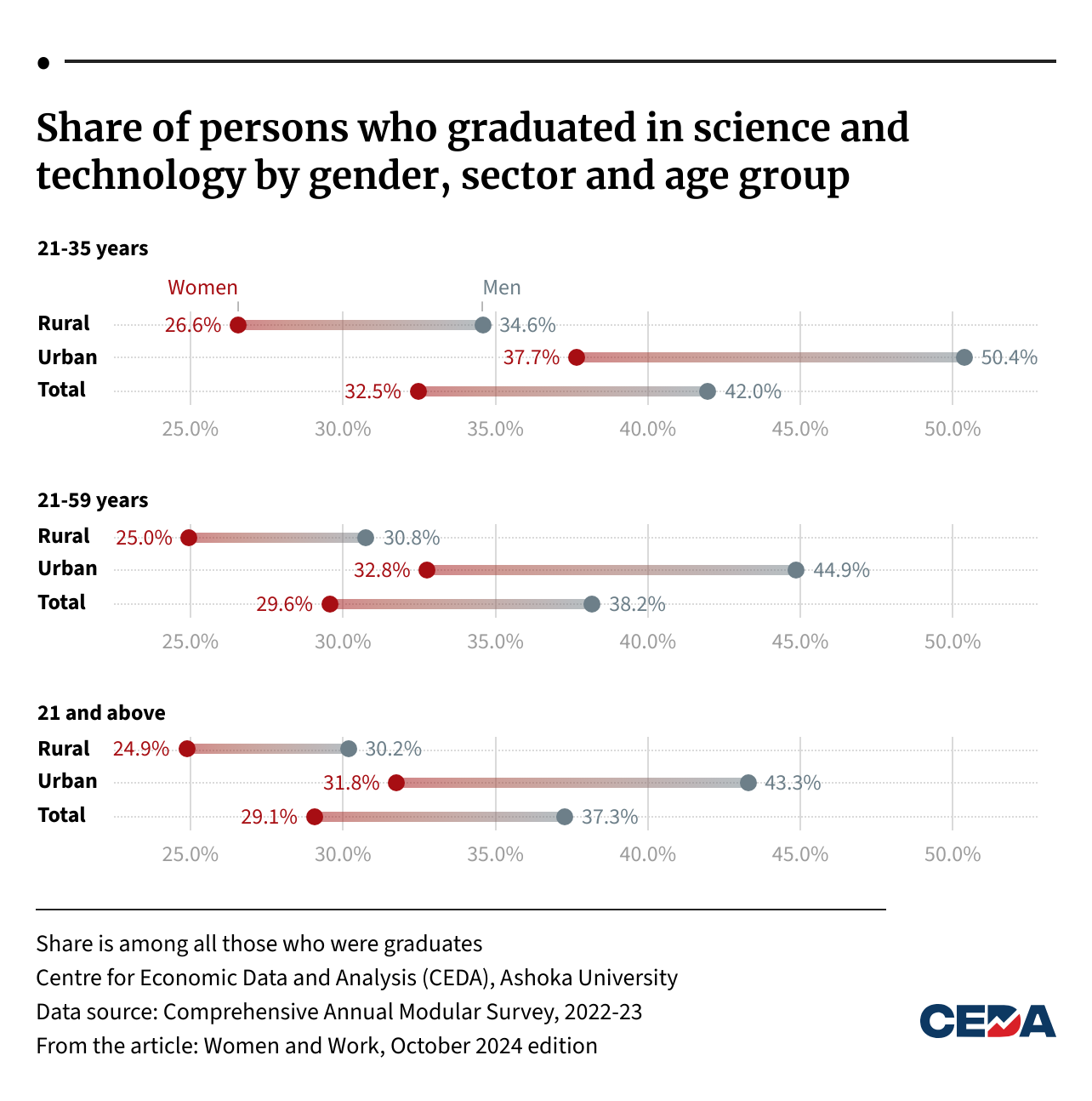

How many men and women are graduates in science and technology? Among those between the age of 21 and 35 years, this share stands at 42 percent and 32.5 percent respectively, data from the Comprehensive Annual Modular Survey, 2022-23, released earlier this month shows. Observe how these patterns vary by sector and age group.

👍 CEDA Recommends

This edition’s recommendations have been curated especially for our readers by Anshumaan Tuteja, Assistant Professor of Economics, Ashoka University.

What’s an essential academic work that you would recommend to someone who is just getting started with working on the subject of female labour force participation?

Anshumaan Tuteja: I would recommend Claudia Goldin’s research in this area. Her 2006 Richard T. Ely lecture, ‘The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women’s Employment, Education, and Family’ explores the shifts in female labour force participation from the late 19th century across four phases that saw women switch from service roles prior to marriage into career oriented full-time roles. The shift in women’s perception about career prospects post 1970s is a revolutionary moment, which had several ingredients. For instance, greater investment in higher education, increase in uptake of science courses, shift in societal attitudes, etc. In another paper titled, ‘A Grand Convergence: Its Last Chapter’, she explores the reason behind the increase in gender wage gap till women reach their 40s. She finds that large within occupation differences can be explained by non-linear effects of hours worked on earnings within some occupations. Flexibility in occupations reduces this effect. Thus, she argues that reducing the gap requires a transformation in job structures to provide more temporal flexibility rather than focusing solely on policies or cultural shifts.

Anything published in the news media recently that shed light on an important aspect about women’s work in India?

The rape-murder incident at the RG Kar Hospital underscores the urgent need for safer workplaces, especially in healthcare settings where professionals dedicate themselves to saving our lives. Safety is fundamental not only for individual well-being but also for retaining women in the workforce. The lack of prompt response from both hospital administration and law enforcement raises serious concerns about systemic accountability. This case emphasises the need for comprehensive improvements to workplace safety measures—not only within healthcare but across other industries—to create secure environments where women can work without fear of harassment or violence.

Is there a film that you can recommend which, in your opinion, does a good job of portraying the world of work from a gender lens?

The character of Ayesha Mehra in ‘Dil Dhadakne Do’ comes to mind. It shows how society discriminates against women’s career aspirations and opportunities. Despite being a successful entrepreneur, her own parents don’t consider her for running their family company as she is married and is believed to be a part of another family. When Ayesha is unhappy with her marriage, her mother asks her to switch her focus from her professional career to her marriage. A few others I recommend include the 2015 Jennifer Lawrence starrer ‘Joy’ for portraying the struggles of women entrepreneurs and ‘Fashion’ released in 2008, which highlights the exploitative work environment of women in the fashion industry.

And a book that did the same?

Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men by Caroline Criado Perez. It provides an in-depth look at how gender biases in data collection and its analysis have shaped everything from office environments to workplace policies, often marginalising or disadvantaging women. Perez uses examples from healthcare, urban planning, transportation, and the corporate world to illustrate how these biases manifest in various settings. For instance, she examines gender differences in workspace design and safety standards. It reflects the unseen ways that workplaces and policies can be structured around male experiences, often leading to unequal outcomes for women.

⏳Throwback

The above table is excerpted from the National Sample Survey Number 8: Report on Preliminary Survey of Urban Employment in 1953. The survey was conducted in Sep 1953 covering towns with a population of more than 50,000 at that time excluding the four big cities of Delhi, Chennai (then Madras), Kolkata (then Calcutta) and Mumbai (then Bombay). It was the first survey of this kind for India, and the aim was a pilot enquiry to help formulate suitable designs and methods of collecting data on employment and unemployment going forward.

The table above gives a snapshot of the urban population by sector and gender. Observe who was in the labour force and to what extent. The report observed:

“Persons ‘not in the labour force’ are proportionately twice as many among females (86.95 percent) as among males (45.42 percent). This is mainly due to the very high proportion of females (45.42 percent) who are engaged in domestic work only; the corresponding proportion for males is only 0.62 percent.”

Here’s some food for thought before we sign off: to what extent has this landscape changed (or not)?

That’s all from us for this edition. Thank you for reading! We will see you next month. In the meantime, if you have feedback, questions, tips, or just want to say hello, feel free to do so by replying to this email, or drop in a word at editorial.ceda@ashoka.edu.in

Curated by: Akshi Chawla for the Centre for Economic Data & Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University. Cover illustration: Nithya Subramanian