Women & Work - what caught our eye in March 2023

News, research, data, and recommendations about women and work - curated by our team

Hello, and welcome to CEDA’s newsletter ‘Women & Work’!

In this month’s edition we bring you news updates from India and the world, some inspiring stories of progress, worrying data on widening wage gaps, a Women’s Day special interview, recommendations from Professor Ashwini Deshpande, and a wonderful throwback to 1948!

To everyone who is new here: At the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis (CEDA), we are working on an ambitious project to understand and find ways to overcome the demand-side barriers that are keeping women out of the workforce.

We are curating ‘Women & Work’ with the hope that it can provoke, stimulate and amplify conversations about women’s participation in paid work in India.

If you agree with our mission, help us reach more readers!

🗞️In The News

The National Sample Survey Office recently released findings from its Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for 2021-22. Our team dived into the data to identify ongoing shifts in women’s work.

After recording some improvement in recent years, India’s notoriously low female labour force participation rate (LFPR) seems to have stagnated, we found. 29.4 percent of women (aged 15-59) were part of India’s labour force in 2021-22, as compared to 29.8 percent in the preceding year. In contrast, men’s LFPR improved from 80.1 percent in 2020-21 to 80.7 percent in 2021-22. You can read more here.

The World Bank released the 2023 edition of its annual report ‘Women, Business and Law’ assessing laws related to women’s economic participation in 190 countries. Only 14 countries across the world have legal equality for men and women across eight areas - mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets and pensions.

Yes, let that sink in. Only fourteen countries! As a consequence, nearly 2.4 billion women of working age still do not have the same rights as men, the Bank observed. In 2022, only 34 gender-related legal reforms were recorded across 18 countries, the report found. This was the lowest since 2001. Read more here.

Global health continues to be delivered by women, and led by men, a new report by Women in Global Health released earlier this month reveals. Even as women comprise 90 percent of frontline health workers globally, they hold only 25 percent of senior health leadership positions.

There have been small pockets of progress - the proportion of Fortune 500 healthcare companies led by women increased from 5 percent in 2018 to 12 percent in 2022. In the same period, however, the share of women health ministers decreased from 31% to 25%, the report has found. Read more here.

💡Research Spotlight

We know women bear a disproportionate burden of household work almost everywhere around the world. But what happens if the women are working in the formal workforce, and also earning more than their husbands? Does that address the skew in household division of labour?

Short answer: It often does not.

Blame “gender deviance neutralisation”. In research literature “gender deviance neutralisation” refers to the behaviour of men and women in situations when they diverge from gendered expectations. Coined by Bittman et al. (2003), this concept argues that when individuals diverge from normative expectations about gender in one realm of social life, they may seek to “neutralise” and compensate for this deviance in other spheres of social life (Schneider, 2012).

One manifestation of this neutralisation is seen in households where women earn more than men. While intuitively one might think that such a situation may mean a redistribution of work, the gender deviance neutralisation effect means often men in such households do even less household work.

Research by Joanna Syrda (2022) published in Work, Employment and Society argues that this gender deviance neutralisation is more likely to happen when mothers outearn fathers (and not just when wives out-earn husbands).

Based on longitudinal data from 1997-2017 comprising married and unmarried-but-cohabiting heterosexual couples in the USA, Syrda finds that “the transition to parenthood results in a larger change in the division of labour within couples than brought by other events, such as getting married or having more children”.

Instead of necessarily leading to more equitable or efficient division of labour within the household, parents’ share of housework exhibits significant gender deviance neutralisation, Syrda observes.

“[P]arents’ gender gap in the division of domestic labour increases in the higher range of women’s relative income. As the gender earnings gap closes and women’s relative income increases, the gender housework gap opens.”

Read the full research here.

💊 Inspiration Dose

How IKEA Retail reached gender balance globally for leadership roles: Forbes

On the road with the first set of women e-bus drivers in Bengaluru: BQ Prime

Delhi’s 100 crore question: What does a free bus ride mean for a woman?: The Indian Express

📊Datapoint

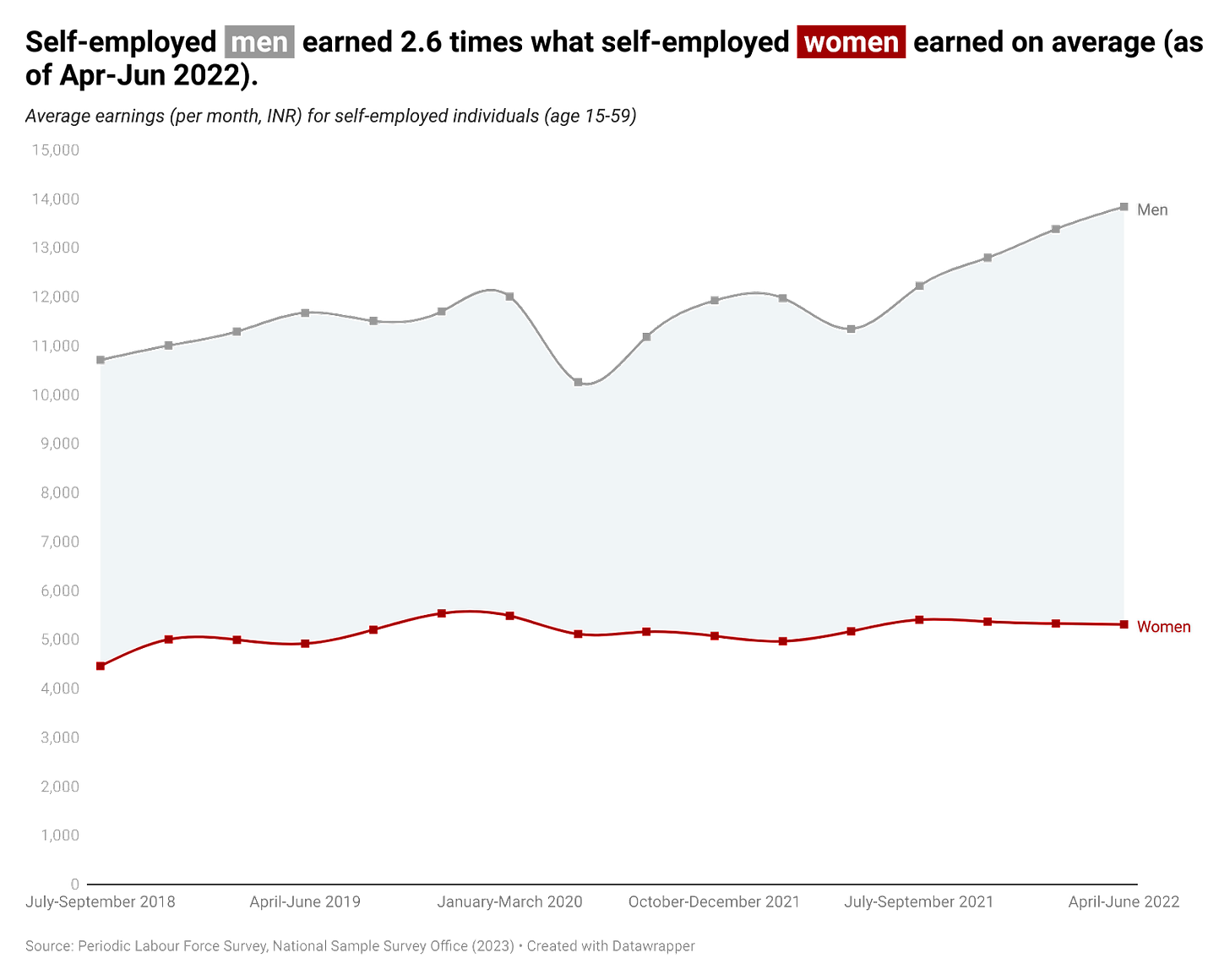

The gender wage gap is real - we know that women earn much less than men across different forms of employment. This gap is the most skewed amongst self-employed workers, data from the PLFS shows.

Consider this: as of Apr-Jun 2022, among salaried workers, women earned INR 14,678 per month on average, while men earned INR 19,722 per month (1.3 times that of women). Those who worked as casual labourers earned much less in general, but here too, men earned more on average. The average daily wage for women working as casual labourers was INR 272, while for men earned INR 408 on average (1.5 times that of women). Among those who were self-employed, the gap was wider. The average woman earned INR 5,311 per month in the Apr-Jun 2022 quarter, while the average man earned 2.6 times (INR 13,843). (Analysis: Dhruvika Dhamija & Akshi Chawla/ CEDA)

👍 CEDA Recommends

This edition’s recommendations have been curated especially for our readers by Ashwini Deshpande, Professor of Economics at Ashoka University and Director at CEDA.

What’s an essential academic work that you would recommend to someone who is just getting started with working on the subject of female labour force participation?

Ashwini Deshpande: Let me recommend something not on labour force participation, but on a much used but little understood word: empowerment. It has become quite a buzzword, and is often seen as a zero-one concept, meaning that either women are seen as empowered or not. However, it never is a zero-one - all of us contain shades of grey where we are more "empowered" along certain dimensions than others. This is as true of the poorest women in the poorest countries as it is about the richest women in the richest countries.

So, what does empowerment mean? Read the gold standard essay in the literature, by the one and only, the inimitable Naila Kabeer.

Kabeer, N. (1999), Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment. Development and Change, 30: 435-464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Anything published in the news media recently that shed light on an important aspect about women’s work in India?

This is linked to the earlier question. It is a very common misconception among elite academics (both Indian and foreign) that Indian gender norms are a monolith, such that gender inequality is hardwired and set in stone. This analysis from Pew Research shows that gender norms are *not* a monolith and have been changing over time!

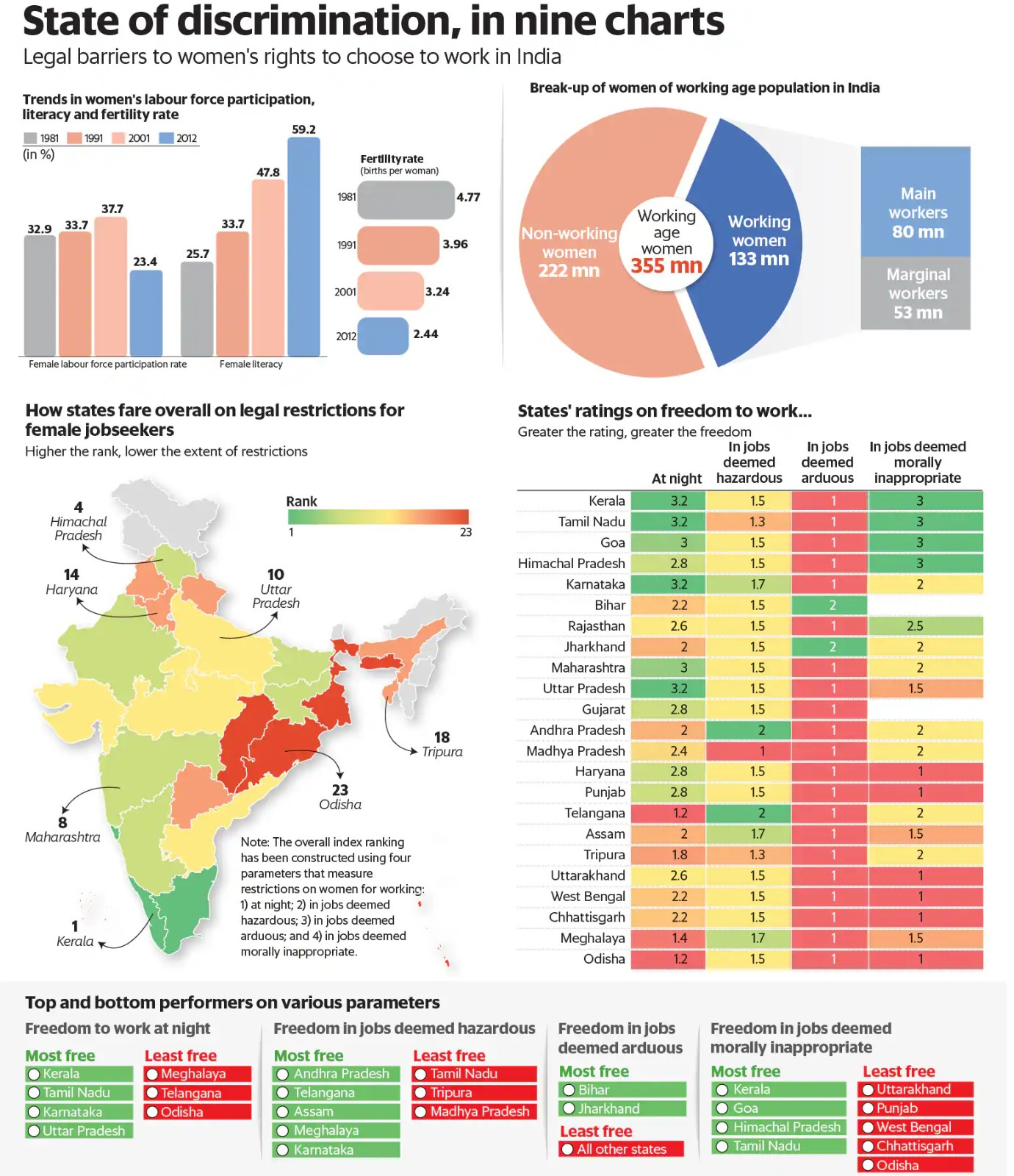

The other piece I would like to recommend is the graph below from this news report ‘The curious case of Indian working women’ by Bhuvana Anand, Baishali Bomjan, and Sarvnipun Kaur published in Mint last year. This report shows there is a great deal of regional variation, again highlighting the need for nuance and detail when we talk about factors affecting women and work in India.

Is there a film that you can recommend which, in your opinion, does a good job of portraying the world of work?

I cannot recommend the Malayalam film ‘The Great Indian Kitchen’ enough! The drudgery, the monotony, the repetitive and never-ending saga of domestic chores, which is seen entirely as a woman's job, is mind numbing. This huge mountain of work is the biggest constraint that prevents women from accessing paid work, if it were available.

I will also recommend the absolutely delightful Hindi film ‘English Vinglish’ with the first female superstar of Hindi cinema, Sridevi. Her family does not value her work enough, despite the fact that she does more than just domestic chores. She actually earns money selling homemade sweets. When she is described as an entrepreneur, she is incredulous as it is the first time someone has accorded her hard work the respect it deserves.

And a book that did the same?

Everyone please read ‘Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men’ by Caroline Criado Perez. It is an eye opener even for those of us who have been studying gender bias and discrimination for a while. It's frightening how the world is designed for men (from AC temperatures in offices to seat belts to bus routes in cities to medical trials) and women are invisible. And again, this is true for *all* countries.

✍️ From Our Desk

Is “Women’s Day” a secret code for a grand shopping festival, or is it a conspiracy hatched by women of the world to come together and discriminate against men? Turns out, it might be none of these! Watch Professor Ashwini Deshpande answer all the questions about International Women’s Day that you wanted answered but were too afraid to ask in this special interview:

⏳Throwback

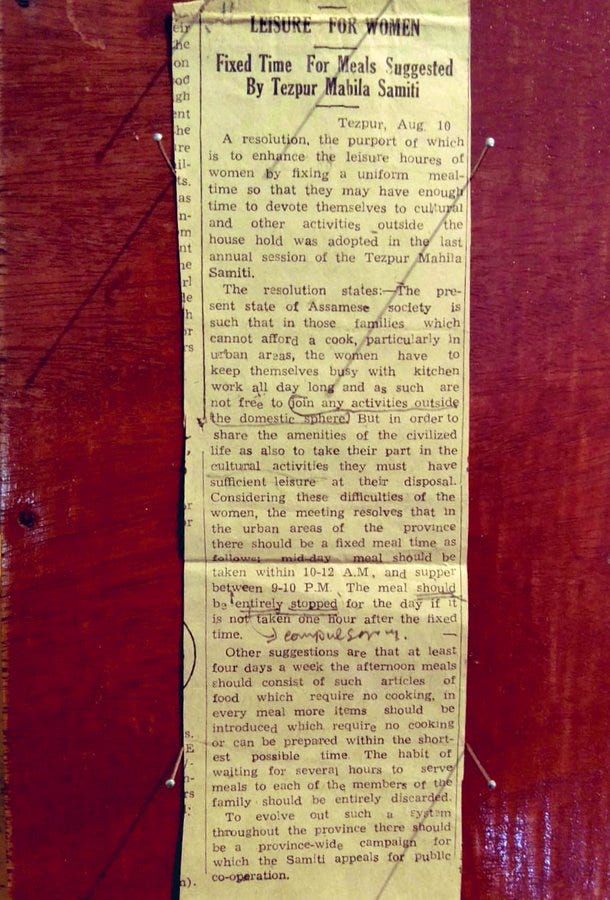

“A resolution, the purport of which is to enhance the leisure hours of women by fixing a uniform meal-time so that they may have enough time to devote themselves to cultural and other activities outside the [household] was adopted in the last annual session of the Tezpur Mahila Samiti.

The resolution states:- The present state of Assamese society is such that those families which cannot afford a cook, particularly in urban areas, the women have to keep themselves busy with kitchen work all day long and as such are not free to join any activity outside the domestic sphere.”

That is an excerpt from a news report published in The Assam Tribune (Aug 10, 1948) talking about the 1948 resolution of the Tezpur Mahila Samiti to fix mealtimes and simplify meals to allow women some free time. As you can expect, the resolution didn’t go down well. Many wrote letters to the editors condemning the resolution.

“What is the duty of a wife towards such a husband who toiled the whole day in scorching sun… Is it her duty to stop his meals when his belly is burning of hunger?”, a reader asked.

The resolution didn’t lead to any change at the time. What would happen if women were to issue something like this today? Any guesses?

Read more about the Tezpur Mahila Samiti in this article from Himal, and in this recent report from The Indian Express.

That’s all from us for this edition. Thank you for reading! We will see you next month. In the meantime, if you have feedback, questions, tips, or just want to say hello, feel free to do so by replying to this email, or drop in a word at ceda@ashoka.edu.in.

Curated by: Akshi Chawla for the Centre for Economic Data & Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University. Illustration and design by: Nithya Subramanian